The Game of Patterns

What an indie video game on geometry

and maths can tell us about Islamic

design

Giulia Gallini

IWA – Islamic World of Art’s Editor-in-Chief The

Islamic Art Historian

Pure Islamic art is something you do not see frequently in video games.

As a matter of fact, some of the video games that have been and are still produced do have references to the Middle East and, in a general sense, to the Islamic world, but the representation of the Orient in video games still relies on an Orientalist narrative, a point of view that counterposes two static entities: the civilised Western world; and the exotic Orient, more or less defined, full of mysteries and danger, enchanting and obscure.

This narrative has been frequently criticized and in some aspects recognized as obsolete. Games such as Prince of Persia, Close Combat, Call of Duty and Halo give the player a stereotyped image of the Orient, depicted as “different from us” in all aspects, without any deeper research and contextualisation. In the world of mainstream video games, Islamic art as such has never had a great role; here and there we can find some hints, but they are superficial references used to contextualise the setting.

That is why it is so impressive that an indie game designer from Iran is developing and will shortly release a totally different game, with a totally different perspective on Islamic culture and the art that it produced.

Engare, designed and developed by Mahdi Bahrami, is one of a kind.

Wall decoration and dome of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque

Isfahan

Photo by Alessandro Longhi

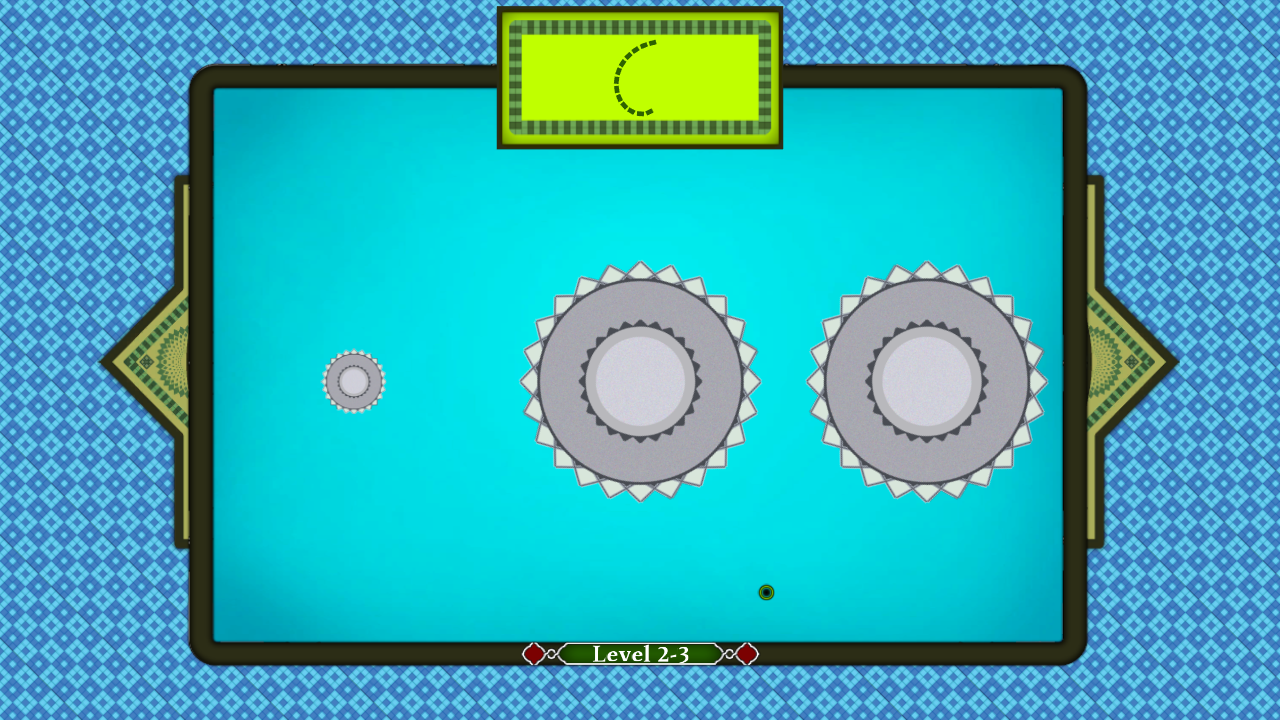

Engare

by Mahdu Behrami

First of all there are no characters engaging in a quest, no plot is developed around one hero. This is due to Mahdi’s personal taste, as he explains clearly: “I don’t like games with a plot, they are like movies. I prefer games where I have a clear goal, just like Tetris: games following mathematical and geometrical rules”. And actually if you have to compare Engare to another game, it is more similar to Tetris than to Call of Duty.

In Engare the player is confronted with moving, usually rotating, objects; pointing one part of the moving object one can see the line that it creates. The aim is to create a given shape. You draw it, you win.

His video game stands out also because of the focus on Islamic art and its pattern. Again, the personal taste and biography of Mahdi play a crucial role in his decision to use maths, geometry, and pattern . Born and raised in Isfahan, his cultural background is imbued with Islamic art.

Coming from Iran, Mahdi has a great and long historical past in which to find inspiration for his game. His Iranian friends at Dead Mage Inc., for instance, developed Garshasp, a third-person action-game set in pre-Islamic Persia, with numerous references to Zoroastrianism and Iranian mythology.

His choice of Islamic art was determined mainly by Mahdi’s love for maths and geometry; the repetition of patterns in Islamic art, ruled by mathematics and geometry but nevertheless enchanting and pointing to the infinite is something that has always fascinated him. The cultural and political moment we are living in pushed him even more to go on with this subject: “People are scared, everything that is Islamic seems to be evil nowadays. I wanted to show that Islam in itself has nothing wrong and can produce something beautiful. I wanted to underline the Islamic aspect of the game. I have decided to release it worldwide and at the beginning, instead of showing a logo, I have decided to write ‘In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate’.

In Iran it is common: everything starts with an invocation to God, and I think if I would have released the game only in Iran I would have omitted it. But since I’m releasing the game outside Iran, I want to keep the initial dedication to God.” And he adds cheerfully: “When people will open the game, they will probably feel uneasy reading ‘In the Name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate’, but when they’ll start to play, they’ll realise nothing is actually wrong with Islam”.

But again, the main reason that pushed Mahdi to pursue the design of Engare is geometry.

“In school I was interested in geometry and maths. I remember my teacher explaining how a rolling ball can draw lines and shapes.” He then developed the concept of shapes created by moving objects, and at the age of seventeen he released what can be considered the ancestor of Engare: Everything can draw!. “You see, it is very simple and has nothing to do with Islamic art, but simply with geometry. It’s colorful and funny. The principle is the same: objects moving and creating shapes.”

When he launched Everything can draw!, his attention was focused on geometry. The connection with Islamic art came later. When reading an article published about his game, he started to realise the connection and eventually he decided to develop it.

Engare

by Mahdu Behrami

The decorative patterns on the niche of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque

Isfahan

Photo by Alessandro Longhi

The shapes the game creates seem to be the prototypes from which one can draw the intricate and repetitive patterns so typical of Islamic art. When asked if there was a study behind the shapes we find in the various levels, Mahdi innocently and blissfully admits, “I chose the shapes quite randomly, trying to produce with the moving objects shapes that I found interesting. Then, when the shape created the pattern I realise they were similar to something I had seen before, for instance the decorated domes in the mosques I had visited in Turkey and in Iran. But I did not use to take an image of an artwork, recognising the basic patterns and then reproduce them in the game. It was a happy coincidence”. When comparing the patterns created by the video game with Safavid and Ottoman art, a resemblance is actually apparent, but when compared with patterns developed in other parts of the Islamic world, like Spain or Egypt, things are different. No clear connection is present. Islamic art is mostly known for the decorative patterns it produces, from Spain to India. The omnipresence of the decorative geometrical patterns has justified and fuelled, together with other features, the definition of “Unity in Diversity”. According to this paradigm, Islamic art is basically homogeneous and shows its typical characteristics regardless of the origins and periods of production. Engare and the way the game produces patterns may contrast with this view, in a way. Also, usually when studying the patterns in Islamic art, and their design, everything is made thanks to ‘statics’ tools: rules and compasses. In Engare, it is the movement that creates patterns, and the patterns created are those of a certain tradition related to the eastern Islamic world. As Mahdi puts it, “We are not one hundred percent sure of how the patterns were actually designed, if thanks to a rule or using moving elements such as the ones reproduced in the videogame. We can assume that in Iran the movements of objects and the shapes that this movements create could be studied: in the work of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (Mashhad, 1201 – Baghdad, 1274) the movement of the circles were studied. It can be that they were also used for the creation of patterns.”

And citing the work of Peter Lu, researcher at Harvard studying physics and also Islamic geometrical patterns, Mahdi explains that “we are not one hundred percent sure of how the patterns in Islamic art were created, using which tools and following which rules”. And the intriguing question is: can a video game shed light on the design of patterns in Islamic art?

Engare is an appealing and enchanting game. Just like Islamic art, it can be enjoyed on many different levels. A kid can enjoy the rotating and mesmerizing elements that create shapes, a graphic designer enjoys the ease with which patterns can be created, and even those who are less familiar with the Islamic world will love the atmosphere created by the visual concept and the evocative music, composed by the Iranian musician Moslem Rasouli. Last, an expert in Islamic art can possibly draw new and challenging conclusions on the creation of patterns.

And definitely, everyone would enjoy playing with it and with its shapes. Looking forward to the official release

The decorative patterns on the niche of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque

Isfahan

Photo by Alessandro Longhi

Engare

by Mahdu Behrami